The idea that each of us has a personal preference on the type of instruction media we believe we learn best, also known as our learning style, has been widespread in the field education for many years. Some are referred as visual learners, others as auditory learners, or kinesthetic learners, and so on. The concept is pretty simple and might make sense in the surface. If someone’s learning style is auditory, they will learn best when they receive instruction through speech, music, or any other audio media. Similarly, if their learning style is visual, instruction using words and pictures would be the most effective, and if they are kinesthetic learners instruction should be in the form of movement or hands-on activities. However, research does not support this simplistic line of thinking.

In fact, in an in-depth investigation of current research in the field, Pasher et al. (2009) concluded that there is little to no support to such claims. Their findings indicated that tailoring instruction to a particular learning style will not necessarily enhance learning and some studies even contradicted this hypothesis and proved it to be a harmful practice. This does not mean that learning styles do not exist or that people do not have preferences when it comes to the method of instruction they feel more comfortable with. It only means that matching an individual’s learning style to the method of instruction is not the solution to improve learning outcomes.

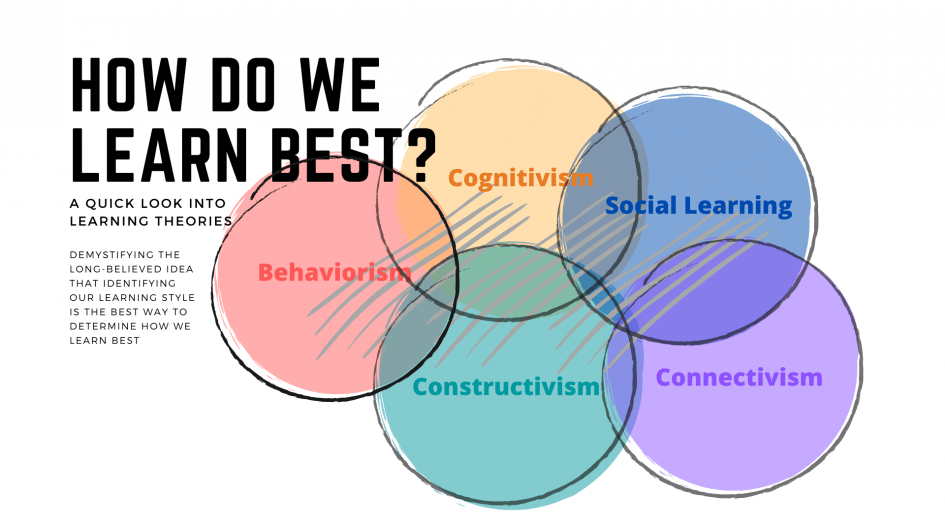

What is the solution, then? How do we provide instruction that is effective and addresses learner’s individualities? To answer this, we need to take a deeper look into the content we are to teach as well as consider the underlying psychological processes explained in each learning theory. Put in simple words, the most effective method of instruction does not depend on the individuals’ learning style or preferences, but rather on the nature of the content itself.

Behaviorism focuses on human behavior that can be observed and measured as it responds to a stimulus. In essence, all behavior is learned and, therefore, can also be unlearned or replaced by new behaviors (Standridge, 2010). Skinner’s experiments also led to the conclusion that behavior can be manipulated by associating it to positive or negative reinforcements, both of which increase the frequency of the behavior, and positive or negative punishments, both of which decrease the frequency of the behavior. No matter what your beliefs are or how opposed you feel towards behaviorist ideas, there is no denying that we learn by responding to stimulus and that the feedback we receive will reinforce a response or make it fade away. Even our body uses this methodology. If we touch a surface that is very hot, an automatic response tells it to let go of that hot surface immediately. We learn from that experience and avoid touching any hot surface in the future. So, how can behaviorism help us select a method of instruction that is effective and appropriate to the content we are teaching? Behaviorst learning strategies have proven effective for learning that involves discrimination (recalling facts), generalization (defining and illustrating concepts), associations (applying explanations), and chaining (automatically performing a specified procedure) (Ertmer & Newby, 2013). Behaviorism also helps us determine the desired learning outcome and plan instruction accordingly (Ormrod et al., 2009). Look at what you are about to teach and think of what observable behaviors will prove or demonstrate that your learner has absorbed the material. Lay out the steps to accomplish each skill and provide feedback and reinforcements that can guide your learner to success.

Cognitivism focuses on the study of mental processes through scientific method and abstraction from behavior (Atkisson, 2010). In other words, cognitivism looks at how we perceive, organize, store, connect, and retrieve information and what influences such mental processes to improve or hinder learning. According to Omrod et al. (2009) cognitive learning processes involve three types of knowledge: (1) declarative (knowing that); (2) procedural (knowing how); and (3) conditional (knowing when and why). Being able to consciously apply this knowledge is referred to as metacognition, a skill that is crucial to the development of critical skills such as concept learning, problem-solving, and transferring of knowledge (Omrod et al., 2009). When teaching concepts that involve higher-order thinking, cognitivist taxonomies like the one proposed by Dr. Benjamin Bloom, can provide a better suited teaching methodology. Bloom identified a hierarchy of cognitive processes, from mere acquisition of knowledge, to its comprehension, application, analysis, synthesis. and evaluation. For example, if teaching students about World War II, a teacher could start by exposing facts and having students read and acquire that knowledge, then there should be activities and interactions that deepen students’ comprehension, until they are able to apply, analyze, synthesize and make bridges and connections with their previous knowledge in order to evaluate the impact of WWII in the world we live today. Using cognitivist ideas as a foundation to the teaching strategies in these kinds of more abstract contents will be much more effective than a simple stimulus-response approach. In this case, pre-determining all learning outcomes could be a guide for the instructor, but it could ignore the individual mental contributions and narrow down the scope of the learning content.

Constructivism focus on the idea that learning is an active process and “human beings construct knowledge by giving meaning to current experiences in light of prior knowledge, mental structures, experiences, and beliefs” (Jerkins, 2006). Learning occurs when learners are actively involved in the process of constructing meaning and knowledge rather than passively receiving information. Some contents will have a more lasting impact or a better learning outcome if taught through a hands-on approach, manipulation of materials, elaborations and conclusions deriving from experience. Cognitivism stimulates the use of problem-solving skills that transcend information given and creates assessments that focus on transference of knowledge and skills into different contexts. If teaching addition to young children, for example, giving them manipulative materials where they can touch, count, and concretely experience that two plus two is four and construct their own understanding of the problem would be much more effective than simply telling them or making them memorize the equation. This teaching strategy would not only target “kinesthetic learners,” instead, all learners could benefit from it.

Social learning theories complement the previous learning theories in the way that it acknowledges the role of human interactions in the learning experience. Learning also occurs through modeling, observing and imitating others, and through Interactions with persons in the environment. Interpersonal interactions, cultural-historical values and beliefs, along with individual factors play a part on what and how we learn. According to Vygotsky’s propositions, in order to be most effective, learning should happen within learners’ ZPD (Zone of Proximal Development), or the difference between what a learner can do without help and what he or she can achieve with guidance and encouragement from a More Knowledgeable Other (MKO), who could be a teacher, an expert, or a more knowledgeable peer (Laureate Education, Inc., n.d.). Social learning strategies would be more appropriate for teaching contents that require modeling of a skill or expert guidance, for example. Collaborating with peers and exchanging ideas have also been found to be effective ways to improve learning and should be incorporated, or at least considered, when planning instruction of all sorts of subject matters.

Connectivism is probably the newest trend in education and, although it is not widely accepted as a learning theory, it brings to the plate some relevant considerations regarding learning in today’s technology-driven society. According to Siemmens (2015), the founder of the Connectivism movement, learning occurs by connecting specialized nodes or information sources. Learning may take place internally, externally (through human interactions), or it may reside in non-human appliances (Siemens, 2005, cited by Davis et al., 2008). Throughout our lives, we build a series of networks based on our experiences and when faced with a new situation (or learning opportunity), we make interactions and cross-referencing between these networks and the outside world to construct new knowledge. One important premise in Connectivism is that reality is constantly shifting and something that is right today may be wrong tomorrow. Therefore, there is an inherent need of continuous adjustments within these learning networks. Probably one of the greatest implications for education is the fact that “as knowledge continues to grow and evolve, access to what is needed is more important than what the learner currently possesses” (Siemens, 2005). Technology offers more stored information than any mind can attempt to retain. This means that simple memorization of facts, names, and dates have become somewhat irrelevant. What you do with this information, how you make connections across internal and external networks, and how you apply this knowledge to problem-solve is what really matters. At the same time, the insurmountable amount of knowledge available can be overwhelming and being able to discriminate between relevant and irrelevant information becomes equally crucial. Highly complex tasks, where there is need for critical thinking, problem-solving, creation of new knowledge through organization and association of information across multiple domains are typically a teaching content that should involve technology as a learning tool.

To conclude, I always thought that this quote from the Chinese philosopher Confucius was the best way to describe how I learn best: “I hear and I forget. I see and I remember. I do and I understand.” I have a strong personal preference for doing things with my own hands, writing, drawing connections, making meaning and building knowledge from experience. I falsely believed that I would always learn best if a content was taught with a hands-on approach. However, after reflecting on each learning theory, I find that this is not particularly true to every learning experience. I never had to experience war, drugs, or alcohol addiction to learn that they are harmful to me. Reading about it, watching the news and listening to tragic testimonies of people who have been through these situations was as effective as if I had experienced them, and certainly much healthier and safer. On the other hand, when I was being trained to be a teacher, observing other teachers and getting my feet wet in preparing lesson plans, teaching, getting feedback from my teachers and students, as well as reflecting on what was effective and what needed improvement, proved to be much more relevant and long-lasting than simply reading about learning theories or hearing about other teacher’s experiences. I have a tendency to prefer learning by myself, however, there is no denying that some contents are much more effective when learned in a group through collaboration and exchange of ideas. I could say that I learn best when content is aligned to my personal goals and when I feel it is relevant to my life or line of work. I learn best when I receive constructive feedback and guidance, when I can self-direct my own learning experience, and when I am motivated to learn. Finally, I learn best when I am able to incorporate technology into my learning experiences. Online learning has become more than essential in how I learn. I use the internet for database search, for collaborating and exchanging ideas on a variety of platforms (from personal social media interactions to professional teamwork projects), for watching or producing video tutorials, movies, and so on. Computer softwares and apps help me record information and create lessons, designs, and share this knowledge with a greater audience than I could ever have dreamed of. So, if today I was asked “How do you learn best?” my answer would be “It depends on what I am learning!”

References

Behaviorism vs. Cognitivism. Ways of Knowing. Michael Atkisson. (2010, October 12). https://woknowing.wordpress.com/2010/10/12/behaviorism-vs-cognitivisim/.

Davis, C., Edmunds, E., & Kelly-Bateman, V. (2008). Connectivism. In M. Orey (Ed.), Emerging perspectives on learning, teaching, and technology. Retrieved from https://textbookequity.org/Textbooks/Orey_Emergin_Perspectives_Learning.pdf

Ertmer, P. A., & Newby, T. J. (2013). Behaviorism, Cognitivism, Constructivism: Comparing Critical Features From an Instructional Design Perspective. https://northweststate.edu. https://northweststate.edu/wp-content/uploads/files/21143_ftp.pdf.

Jenkins, J. (2006). Constructivism. In Encyclopedia of educational leadership and administration. Retrieved from httt://knowledge.sagepub.com.ezp.waldenlibrary.org/view/edleadership/n121.xml

Laureate Education (Producer). (n.d.). Theory of social cognitive development [Video file]. Baltimore, MD: Author.

Ormrod, J., Schunk, D., & Gredler, M. (2009). Learning theories and instruction (Laureate custom edition). New York, NY: Pearson.

Pashler, H., McDaniel. M., Rohrer, D., & Bjork, R. (2009). Learning Styles: Concepts and Evidence. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 9(3), 105-119. doi:10.1111/j.1539-6053.2009.01038.x

Simenes, G. (2005). Connectivism: A learning theory for the digital age. International Journal of Instructional Design & Distance Learning. 2(1). Retrieved from http://itdl.org/journal/jan_05/article01.htm

Standridge, M. (2010). Behaviorism. In M. Orey (ed.), Emerging perspectives on learning, teaching, and technology. Retrieved from http://textbookequity.org/Textbooks/Orey_Emergin_Perspectives_Learning.pdf

Leave a Reply